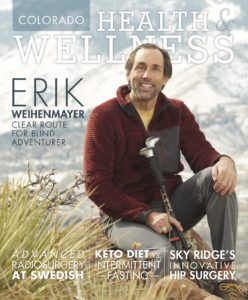

Clear Route for Blind Adventurer | by

Colorado’s Erik Weihenmayer pioneers ‘No Barriers’ from whitewater to ice and rock.

Short, swaying waves lapped against the kayak’s belly. The flowing water slightly hummed against the boat’s walls and reached the legs of professional adventurer Erik Weihenmayer, who alternated his paddle side-to-side. He felt the sunshine disappear behind the Grand Canyon’s rim. His crew chattered, as they pulled up to banks of Redwall Cavern, a ginormous alcove and beach the size of a football field.

Weihenmayer dragged his boat onto shore. He dug his toes into the sand, clicked his tongue, snapped his fingers, and sprinted full-force ahead. Weihenmayer was sure he couldn’t collide with any obstacles here — despite being blind.

Everest summit

At age four, Weihenmayer was diagnosed with retinoschisis, a rare condition in which an area of the retina separates into two layers. Less than a decade later, he completely lost his sight. As an athletic, active kid, he eventually found rock climbing.

His passion for scaling mountains would shape his entire life.

World-Class Adventurer

Weihenmayer’s iconic stature as a world-class explorer burgeoned at age 32, when he became the first blind person to summit Mount Everest in 2001 — and he didn’t stop there.

He completed the Seven Summits, reaching the top of the highest peak on each of the seven continents; rock climbed the 3,000-foot Nose technical route on El Capitan; and ice climbed Losar, an equally-long ice-waterfall in the Himalayas. He learned to skydive, paraglide and kayak, all while steering his own vessels. He skis backcountry and navigates expert runs in-bounds.

And that’s the abbreviated list of his accomplishments.

The trailblazer’s most herculean feat to date, however, might be the trophy whitewater mission that surrounded Redwall Cavern.

In September 2014, Weihenmayer, then 45, paddled the entire length of the Grand Canyon: a 277-mile run along the Colorado River, one of the most prized, challenging waterways in the country. The epic passage entails a notorious boxing-ring of swells, drops, whirlpools and several hundred rapids — which swing into class IV — that can swallow an entire raft let alone a kayaker.

“In climbing, you can stop and collect yourself. You can’t do that with kayaking,” says Weihenmayer. “Kayaking pushes the uncontrollable to a higher level than in climbing. The experience becomes more about letting go of what you can’t control while not letting fear consume you.”

Fortunately, Weihenmayer is committed to the due diligence that’s needed to reach his audacious pursuits. Captured in the documentary, “Weight of Water,”which kicked-off a tour in Colorado in March 2019, Weihenmayer trained for six years — including an 11-day trip to paddle half of the Grand Canyon’s biggest rapids — before he put-in at Lee’s Ferry.

“I wanted to know if this was a realistic goal,” Weihenmayer says. “I don’t take crazy, massive risks.”

For the voyage, he was joined by friends: a crew of expert kayakers including Lonnie Bedwell — the Grand Canyon’s first-ever blind kayaker — and river guide Harlan Taney, who paddled behind Weihenmayer and provided commands via a waterproof radio headset. “Harlan has this beautiful sense of trusting the journey, even though the waves can slam you. I’ve learned great lessons from him,” Weihenmayer says.

Letting Go and Letting Trust Win

In a strange paradox, losing his ability to see vastly enriched his life, due to the deep bonds that he shares with people.

“When you go blind, you have to let your ego go. It’s a hard lesson, but you’re not going to accomplish anything through stubborn independence,” Weihenmayer says. “It’s been a backwards gift in my life. Because I’ve had to do activities with other people, I’ve been so lucky to find amazing biking, skiing, and climbing partners and to connect with them in ways most people don’t. They trust me and I them.”

Teamwork is a fundamental component in Weihenmayer’s formula of success, which is coined as, the “No Barriers” approach to life.

“We all want to live a big life and barriers stagnate you. It’s not motivation that’s the problem. People need the tools, mindset and team: that’s the formula. Then, the ultimate goal is stepping outside of yourself to elevate the world around you,” Weihenmayer says.

To teach this mental framework, Weihenmayer co-founded No Barriers USA in 2005. The nonprofit organization uses transformative outdoor experiences to coach people with challenges — be it physical, emotional, psychological, socio-economic, or otherwise — so that they can achieve their individual and collective potential. Each year, the curriculum helps 10,000 students of all ages to dissolve mental barriers, accomplish their goals and adopt a give-back ethos.

“At the No Barriers Summit, we’ve shown people how to manage pain beyond prescription drugs,” says Weihenmayer. “We’ve helped immobile people drive Action Trackchairs, so that they could charge up extreme, steep terrain and summit mountains. Those triumphs are 99 percent of what keeps me excited about life and the ‘No Barriers’ spirit.”

Mind and Body

Beyond his philanthropic work and mental training, Weihenmayer follows a physical training routine, hones his skillsets, cultivates strong teams, and creates logistical systems for his outdoor travel.

In an ebb and flow, he also recovers well at home in Golden, Colorado, between expeditions. He prioritizes a plant-based diet, lets his weight fluctuate, relaxes, cross-trains, and rides bikes with his wife and kids. When it’s go time, he’s ready to focus.

“I’m 50 years old now. My knee gives out sometimes. Life isn’t perfect, but I train a ton,” says Weihenmayer, who shifts his gym regime to support each season and objective. Throughout the year, he regularly rides a tandem mountain bike, climbs, and skins uphill. “I even lift weights and do hideously boring things like two hours on the StairMaster. I train hard.”

Next Crests

This year is fueled by redemption. For the spring season, his mind’s eye is set on ice climbing La Pomme d’Or, a 1,200-foot ice-waterfall that fills-in on the periphery of Quebec City in Quebec, Canada. “It’s the ‘Big Apple,’ and a stunning, steep climb,” describes Weihenmayer. To prep, he ice climbs, does pull-ups, and practices hanging exercises with ice tools.

The project will be round two. “I tried La Pomme d’Or once. The conditions were bad. Ice the size of bowling balls was coming down on our faces and exploding everywhere,” he recalls.

Later this year, in November, he plans to return to Ama Dablam, a 22,349-foot high Himalayan peak, also known as “The Mother’s Jewel Box.”Weihenmayer first attempted the ascent 18 years ago with climbing partner Eric Alexander. The duo was ice climbing mid-plot when they were caught in a seven-day storm.

“[Alexander] had to get down, because he was starting to gurgle, a sign of hypoxia. On the descent, he fell 150 feet — it was amazing he lived,” Weihenmayer says.

At basecamp, the team hand-pumped air into a hyperbaric chamber for three days to support Alexander, which kept him alive until a sliver in the sky was wide enough for the helicopter evacuation. His survival was miraculous: Pulse oximeter values beneath 90 percent are considered low. Alexander’s reading was at 47 percent.

The ensuing year and Alexander’s recovery was extremely taxing. But, as comrades, Weihenmayer and Alexander didn’t allow adversity to become a permanent barrier for their ambitions. A year later, the two crested Everest, and their cohort set a world record for the most team members — 19 out of 21 — to reach the summit in a single day.

“Everyone had a mission to get me to the summit, and that gave everyone the energy to rise above themselves,” Weihenmayer says. He attributes his and Alexander’s cooperative progress to their lessons learned on Ama Dablam.

“It was healthy for us to learn how we handle crisis together. It was a secret ingredient for the next year,” Weihenmayer says. “You don’t start as a team. When the mountain erects a barricade in front of you and you cross through it as a team, you grow as a team.”

In November, Alexander plans to join Weihenmayer for their second effort up Ama Dablam. Together, they’ll face and stand on top of the crux — the prize but never the full picture.

“Wilderness and mountains are beautiful,” Weihenmayer says, “but they throw hardship at you. It’s so much nicer to be there with the people you love.”

Erik Weihenmayer is the subject of the new, award-winning documentary “The Weight of Water,” which chronicles the adaptive adventurer’s physical, mental and emotional journey kayaking the harrowing whitewaters of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon.

Tags: Adaptivesports, ErikWeihenmayer, NoBarriers

Comments

Leave a Comment

Please be respectful while leaving comments. All comments are subject to removal by the moderator.

[…] Read the full story in print and on healthwellnesscolorado.com. […]